Lessons from Lacan’s Practice – Everyday Psychoanalysis, from the Classroom to the Boardroom (II)

Let’s start this article not with Lacan but with this guy:

His name was Hardy Amies. In the last post we looked at how the imaginary is never simply imaginary, that the realm of images has to be supported by a symbolic validation or sanction. We can continue this theme with reference to a beautifully Lacanian truism made by the man above, encapsulated in one of his throwaway remarks: “Everyone wants to give you something. You just have to find out what it is.”

Hardy Amies, ostensibly, lived in the imaginary register – he was a fashion designer. Indeed, one of great note, rising to become dressmaker to the Queen of England.

But Hardy was not just a fashion designer. He was also a spymaster. As well as spending his formative years making dresses, during the Second World War he was part of the British intellgence service’s Special Operations Executive and orchestrated a campaign of counterinsurgency against the Nazis in Belgium known by the codename Operation Ratweek.

More on him later.

But first, with his remark in mind, let’s look at some of the ways in which people talk about themselves without talking about themselves.

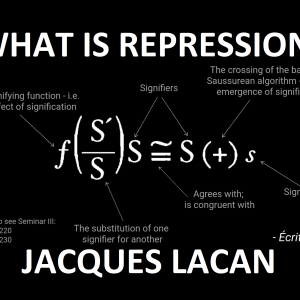

Lacan’s adage that “a signifier is what represents the subject to another signifier” (Écrits, 819) implies a conception of the subject as an effect of the signifier, subject to a division by what Lacan repeatedly calls the “defiles of the signifier” (ibid, 618, 811, 895). This is why Lacan writes the subject – S – with a bar through it – $. One implication of this is that what someone says carries a signification quite different to the one they intended. Very often, they say more about themselves than the thing that they are – ostensibly – talking about. When it comes to the unconscious we do not speak, we are spoken.

Talking about yourself without talking about yourself is an extremely common phenomenon that all Lacanians will easily be able to recognise in everyday life. Very often, if we allow someone the time and space to talk about pretty much any topic they choose we find that the conversation eventually starts to shade off into something that, although apparently unrelated or impersonal, is actually very specific and very telling of their own circumstances. Quite unbeknownst to them, they have found a roundabout way of talking about themselves or how they see themselves.

Here’s a beautiful little anecdote from Lacan’s practice that illustrates how Lacan played on this fact to make it a lever in a psychoanalysis. It’s from an anecdote reported in Jean Alloch’s Les Impromptus de Jacques Lacan (Lacan’s Quips). A man comes to see Lacan for a psychoanalysis. We can imagine that Lacan asked him about himself – his ‘story’ – in whatever way he wanted to express it. At some point the conversation went like this:

The analysand:

– My grandmother was very beautiful…

Lacan:

– That’s absolutely right!

(Les Impromptus de Jacques Lacan, Jean Allouch, p.108).

Why did Lacan interject at this point? He could certainly never have known the grandmother in question, and to abruptly interrupt his analysand before he or she had a chance to finish their sentence might strike us as rude. But what Lacan was doing was very clever. His sudden proclamation of conviction about the grandmother’s beauty was a ruse to get his patient to hear the absurdity in what the latter was saying – namely, the assumption about his grandmother that had until then gone unquestioned, that was treated as completely axiomatic.

This was one of Lacan’s greatest tricks – getting the subject to receive his own message from the other in inverted form. That Lacan restates this little maxim again and again in his Écrits, – from the Overture right at the start on p.9, to pages 41, 56, 298, 353, 420 and 439 (French pagination) – shows that it was a real hallmark of his practice.

Let’s take an example from everyday life of where the subject is the recipient of their own message in inverted form.

When someone offers you advice it is absolutely axiomatic that the advice will not pertain to you but to the person giving it. A few years ago I was having drinks with a colleague who wanted to impress on me the importance of not promising too much to your boss in the workplace. The words he used were “Never commit, never commit”. I would have taken his advice a lot more to heart were we not out that night to celebrate his marriage the following week. I took it that, under the guise of advice, he was talking about himself rather than to me.

Here’s another example from Lacan’s practice of how he was able to get his analysand to receive his own message in inverted form. Allouch titles it Vacance (note the singular):

We are on the last day of the year. The analysand:

– Bonnes vacances!

Lacan:

– Because you, you are going on holiday?

(Les Impromptus de Jacques Lacan, Jean Allouch, p.115).

The abruptness of Lacan’s reply is odd. Firstly, why did he respond at all? A leavetaking like this is most of the time not read as anything more than a simple pleasantry. In questioning it however we are left wondering what he thought the analysand was on holiday from, or from whom. Without the context of the analysis we don’t know. But Lacan’s response suggests that he thought his analysand was talking about more than simply going on holiday.

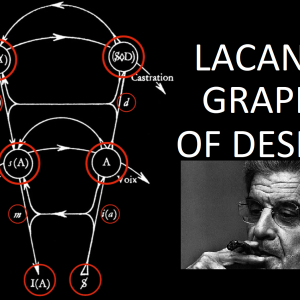

Whenever Lacan talks about desire there is an important caveat to be added – we can’t speak in the first person about our unconscious desire. Desire is something that is articulated in the margins, in the space between two utterances. This is why Lacan makes the distinction between demand and desire. Desire uses demand as a Trojan horse. When we are confronted with anything that looks like a demand, we have to divine the desire that may lie behind it. Very often, the way to do this is to look for a displacement. Displacement indicates that there is something that cannot be expressed in the form of a demand (in the form, ‘I want…’, for example).

Many years ago I applied to do a psychoanalytic training with a group in London. As part of the application process I was asked to submit a CV and to go to an interview conducted by one of the analysts overseeing the training programme. The first question I was asked was, ‘Why do you want to be a psychoanalyst?’ I responded as best I could, but the analyst was clearly dissatisfied with my answer. Later, I asked a friend why that might have been and she told me, quite sensibly, that embarking on a psychoanalytic training entailed questioning one’s desire to be a psychoanalyst. The analyst interviewing me had clearly wanted to hear evidence that I had such a desire. But, if we take Lacan’s ideas on unconscious desire seriously, asking the question ‘Why do you want to be a psychoanalyst?’ anticipates a response that is articulated with the first person pronoun. In other words, ‘I want….’

Assuming one’s speech, and the unconscious content it can reveal in spite of oneself, is part and parcel of a psychoanalysis. Lacan got this, and there are two stories from his practice that demonstrate this.

Firstly, an account of an exchange between Lacan and one of his analysands that went as follows:

The patient:

– The voice is not a strange voice; I had the impression of hearing myself; she is behind me, above me.

Lacan:

– You have the impression of hearing yourself, that means that she speaks?

The patient:

– Yes

Lacan:

– How does she speak? She forbids you from saying a word?

The patient:

– Yes… as if she prevented me from speaking… I don’t know how to say.

Lacan:

– Try. Who will speak if not you?

(Les Impromptus de Jacques Lacan, Jean Allouch, p.127).

Secondly:

He lies down on the couch and then, after a short time:

– I have nothing to say…

An amused Lacan responds:

– Well yes! It happens! Till tomorrow, old boy.

(Les Impromptus de Jacques Lacan, Jean Allouch, p.40).

In a psychoanalysis as well as outside it, you are the only one that can tell your story. These anecdotes show us the ways that Lacan communicated to his analysands that the obligation to speak was theirs and theirs alone without being – as is often mistakenly thought to be the proper conduct of a psychoanalyst – passive.

We’ll wrap up by looking at a character whose career intersects nicely with that of the guy we began with, Hardy Amies. Like Amies, Michel Thomas worked in intelligence during the Second World War; like Amies, his knowledge of other languages led him into fieldwork where he was responsible for bringing Nazis to justice; and like Amies, he also went on to become famous for something quite different after the war ended.

While Amies’ later life as a fashion designer could be said to have taken him down the path of the imaginary, Thomas’s took him down the path of the symbolic – he became a world-renowned language teacher. His clientele was drawn from the Hollywood elite of his day – Grace Kelly, Sofia Loren, Bob Dylan, Barbara Streisand and Woody Allen all learned with him.

During the war, Thomas fought first with the French resistance and then with the US Army’s counterintelligence corps (for which he was later awarded the Silver Star). As an interrogator, his method was famed for being very subtle, and without resort to violence. The attentiveness to a person’s speech that he had learned during the war was something he later employed to good effect as a language tutor. The same method, but with a different purpose: getting things out of people that they didn’t know they could say.

Thomas explained his teaching method in this clip as follows: “I will dissect everything into small parts and reassemble it in such a way that everyone will understand everything step by step.” Like Amies’ remark that we looked at earlier, this is very Lacanian. In fact, is this not essentially what interpretation means in a Lacanian sense? To take apart (the) language, the words that one speaks, and dissect this speech in such a way that it will be heard differently, understood differently, by the analysand. From one language to another, from English to French; from one resonance to another, from conscious to unconscious.

Everyone wants to give you something, you just have to find out what it is – Neither Amies nor Thomas were psychoanalysts. Perhaps neither had ever heard the name Lacan much less been troubled by his Écrits. But Amies’ words and Thomas’s actions remind us of another way in which we can follow Lacan’s teaching and practice psychoanalysis everyday.

By Owen Hewitson, LacanOnline.com

All content on LacanOnline.com is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Leave a Reply