Lessons from Lacan’s Practice – Everyday Psychoanalysis, from the Classroom to the Boardroom (IV)

– Lacan, Seminar XIII, 2nd February 1966.

If a stupid question is one that we should already know the answer to, Lacan asked many stupid questions. Here are a couple, as related by two of his former patients:

He had to decide. For months and months he had told Lacan of his love for X, talked about her, of his relationship with her, of her life. In short, he had completely analysed his choice of her….

He arrives in the session to declare, finally:

– I’m getting married next week.

Lacan:

– To whom?

(as related in Jean Allouch, Les Impromptus de Lacan, p.81).

In analysis with Lacan for two years, he is called to do his military service. Lacan:

– So why are you doing your military service?

(ibid, p.44).

Lacan must have known the answer to these questions. This article will look at why he asked them.

Lacan means this more as a critique than as a description. We have a tendency to ask questions having already decided what the answer will be, and this is a point that Lacan makes again and again in his later work (Lacan geeks can check out Seminar XIX, session of 19.01.72; and Seminar XXI, sessions of 02.11.73, 15.01.74, and 23.04.74 for more on this).

Generally speaking, people ask questions not to find out information but only when they believe they know what they are going to find out. Which, in a sense, would make all questions stupid.

How does this happen? Lacan believes that most of the time asking a question is like flicking a light switch. It is our own expectations, or our own desires, that we anticipate being realised:

A response to a question therefore becomes modelled on a ‘stimulus-response’ reaction.

However, in his work of the 1950s and ‘60s, Lacan puts a slight twist on this with the idea that the effect of a person’s speech can be to fix the subject to whom it is directed in a certain position. This brings about a sort of ‘nominative determinism’ on the listener, a petrifying effect that frames them or their response in a certain discourse, a relationship of power or control:

In this last line we see that Lacan counsels his followers to be mindful of this effect. In the context of a psychoanalysis, it can be an especially dangerous business. Elsewhere (Seminar III, p.48) Lacan gives an example of how this works – with the act of saying ‘You are my wife’ or ‘You are my master’ the subject to whom these words are addressed becomes fixed in what Lacan called above a “subjective function he must take up in order to reply to me, even if it is to repudiate this function” (Écrits, 300).

This same idea is expressed in slightly more dubious terms with the notion of ‘frame control’. This is a concept popularised in the amateur field of ‘pick-up artistry’ and in the more quotidian world of business studies:

“He who controls the frame, controls the game”, as their saying goes. The trick for a Lacanian is to avoid ‘framing’ any type of communication in this way. How?

Well-intentioned people know that asking questions is a fundamentally good thing. It demonstrates an interest in other people. After all, whether it be with a colleague at work, your boss, on a date, or with friends or family, if someone doesn’t ask a question of you, and if that question isn’t about you, it can be taken as a sure sign that the person you are speaking to is not really interested in you. Put in Lacanian terms, asking a question is a demonstration that another person respects the singularity of your subjectivity. This is the first simple lesson that psychoanalysis affords us.

But this is not the reason why Lacan asked the ‘stupid’ questions that we started with. For him, the aim of asking a question is precisely not to find out more information about a person or to understand something about them. Lacan was categorically opposed to understanding anything about the patients he took on his couch, and advised his students to do the same. Commenting on Theodor Reik’s book Listening with the Third Ear he asks:

Rather, for Lacan, the point of asking a question is to study the way the question is answered. It would be perfectly legitimate therefore to ask a question even if you know – or believe you know – the answer because the form of the response that you get back will tell you a lot. It is the medium through which unconscious desire is revealed. This is why it’s worth listening carefully to the way that people answer questions about themselves.

Let’s imagine we ask someone what their childhood was like and they immediately start talking about how their parents didn’t have much money. They could have chosen anything to start their response with – what they remember from their long, halcyon summer holidays, fights with their parents, struggles at school – but in the focus on money there is an indication that there is something about this element that is privileged above anything else, simply by virtue of the fact that it is the first thing that occurs to them when you ask the question. This may seem obvious, but an attentiveness to the contingencies of a reply to a question like this is vital in avoiding the problem Lacan drew attention to above.

It’s important to note that unlike with ‘frame control’ there is no attempt at manipulation here. After all, in asking an apparently mundane question about what someone’s childhood was like you are giving them the freedom to account for themselves however they wish. They may choose to interpret an open question in a much narrower way, or by answering with a telling misinterpretation of the question. Regardless, we have to treat with respect the form of the answer they give. Freud makes this point brilliantly in the Introductory Lectures – it would be very unscientific to not accept that x occurs to someone when you ask them about y. It’s like stepping on the scales, seeing the weight displayed, but ignoring the reading on the basis that it could just as well have been any other weight (SE XV, 48-49).

There are numerous anecdotes about how Lacan chided training analysts that did not get this point. Wladimir Granoff relates the story of how his supervising analyst, Francis Pasche, believed that one of Granoff’s patients partook in orgies. Pasche was insistent that Granoff tell his patient that he was making this fact obvious. When Jacques Lacan got to hear this story, he reportedly declared:

(as related in Jean Allouch, Les Impromptus de Lacan, p.215).

In another incident, a young woman told her analyst: “My mother has had four children and me.” Knowing that her patient had three siblings, the analyst decided that she must be confused and that her patient wasn’t counting herself amongst her mother’s four children. She tells this to Lacan who replies with a tone of incredulity and disapproval: “She said it, her mother has had four children and her!” (ibid, p.146).

The question that Lacan asks is not ‘what did she mean?’, much less does he try to to ‘correct’ the patient’s ‘mistake’ on her behalf and work with an assumed meaning. Instead, with a respect for the primacy of the signifier over any assumed signification, what piques Lacan’s interest is the form of the sentence – “My mother has had four children and me” – a pleonasm which might indicate that this woman may consider herself, in some sense, to not be one of her mother’s children, either literally (biologically, to have a different mother) or figuratively (to not feel close to the mother). A more precise interpretation is impossible on the basis of this vignette alone, but what Lacan spies is an indication that something is revealed in the slip which provides an avenue for further investigation.

So far, so Lacanian. But where do we go from here? How might a simple slip like this guide our way to insights into a person’s life, their subjectivity? How does a discrete indication of this sort fit into a person’s psychoanalysis more broadly? The answer, that we’ll look at next, can be found in the fantasy.

Perhaps the most famous question in psychoanalysis is the one posed to Oedipus by the Sphinx. The question here is posed as a riddle, a fact which Lacan does not think is immaterial (Seminar X, 12.12.62). Indeed, at a certain point in his work, Lacan sees neurosis itself as a question, with the form of the question differing according to a person’s subjective structure – whether it is a question about sex, about what it means to be a man or woman, or what it means to be alive or dead relative to a presumed master. To quote from Seminar IV in 1957, the symptom in its essence is nothing more than the means through which that question is expressed:

It’s important to say that Lacan changes his mind later on in his life, ‘generalising’ the symptom to be the expression of a solution rather than the expression of a question, but at this point in his work he finds this rather Levi-Straussian conception to be the most serviceable.

Then, beginning around Seminar VI in the late 1950s, Lacan has the idea that fantasy is a way in which these sorts of questions – ‘deep’ questions about existence and sexuality – are answered.

‘Fantasy’ in Lacanian jargon means something different to how we use it in everyday speech. Fantasy for Lacan is not a wish, it is not some desired or aspired to scenario. If we wanted to avoid the Lacanian jargon we could think of his idea of fantasy – sometimes referred to as ‘fundamental fantasy’ in this context – in the following three ways:

– The fantasy is what we might call a ‘storyline’ – a narrative about our life that may not be consciously realised or is yet to play out;

– The fantasy is a ‘red thread’ – something that denotes a recurrent theme or motif that runs throughout our life, dictating how we see ourselves and want to be seen. This might be manifested in repetitions that seem to recur with an uncanny frequency. Often these appear as acts linked to signifiers that have a special place in the subject’s family history. That is, they are linked to trans-generational phenomena, an extremely fecund area of psychoanalytic research which we have explored elsewhere on this site with reference to the Rat Man’s case history;

– The fantasy is an axiom – this is a term favoured by Lacan himself and used in Seminar XIV, ‘The Logic of Fantasy’. The title here is instructive – Lacan uses ‘axiom’ in the same sense as it is used in logic and set theory, namely as a proposition that is self-evident and is assumed without proof. To slip back into Lacanian jargon, it is a signifier that cannot signify itself, an absolute signification. A number of Lacanians have also picked up on this term and used it to explain the fantasy (see, most notably, Jacques-Alain Miller’s paper ‘Axiom of the Fantasy’ here and Bruce Fink’s chapter on fantasy in his new book, p.47).

Around the late 1950s, the fantasy is treated as the true target of a psychoanalysis: symptoms, slips or signifiers are the threads that allow the fantasy to be either built or uncovered (depending on which reading of Lacan’s work you prefer). For the Lacan of this period, fantasy is the answer a person constructs to the question posed by the Other’s desire. As Jacques-Alain Miller argues, the way this answer is framed can be distilled into a basic formula depending on the structure a person exhibits:

In ‘The Subversion of the Subject’ in the Écrits there is one particular form of this question about the desire of the Other that Lacan favours: Che vuoi? What do you want?

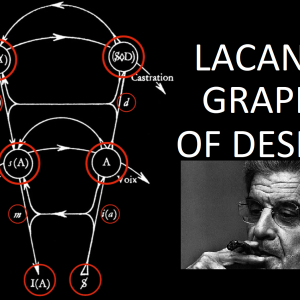

Note that the French expression Lacan uses here – la question de l’Autre – is deliberately ambiguous (credit to Fink for his translation which preserves the original French so as to allow us to hear this ambiguity). It can be read as both a question from the subject to the Other (what do you want?) and also a question sent back to the subject from the Other. Lacan isolates this in the third iteration of his graph of desire:

The curvature of this part of the graph is also deliberately designed to look like a question mark, and Lacan says as much himself (Écrits, 815):

If we trace the path of this question mark from the Other (A), through desire and the question Che vuoi?, it leads to Lacan’s formula for fantasy: $ <> a (ibid, 816). This can be read as a sort of dead end insofar as it is described by Lacan as a point of alienation “that leaves it up to the subject to butt up against the question of his essence” (ibid, 815).

Lacan devotes much of his Seminar VI to a discussion of Hamlet, and one particular part of the play that he zeroes in on is the culminating scene in which Hamlet jumps into Ophelia’s grave and fights Laertes to the death. Lacan was especially interested in this jump into the grave, and it’s something that other Lacanian writers have picked up on (see, for example, Miller’s ‘Presentation of Book VI of the Seminar of Jacques Lacan’ in Hurly-Burly, 10, p.43). Lacan notes that this is a part of the play unique to Shakespeare – earlier versions of the story of Hamlet by other authors contain no trace of this scene (Seminar VI, 18.03.59.).

Perhaps what Shakespeare was attempting to depict with this jump into the grave is something very close to what Lacan would detect as an indicator of the fantasy. In this final jump into the grave that heralds his own death, are we not witnessing an act where Hamlet would “butt up against the question of his essence” (Écrits, 815) in the same way that Lacan defines the fantasy? Whilst for the most part Lacan reads the play as a story of a mourning gone wrong, he nonetheless insists that Hamlet is “a tragedy of the subterranean world” (Seminar VI, 22.04.59.) and so we can perhaps see the final scene as a complement to the first, where “The ghost [of Hamlet’s father] rises up because of an inexpiable offence” (Seminar VI, 22.04.59.)

Back to where we began – stupid questions, and the responses they provoke.

The lesson we can take from Lacan’s practice is that if we see a question not as a request for information but a elicitation of desire there is no such thing as a stupid question. As Lacanian analyst and translator of Lacan’s work Bruce Fink writes,

I once heard an anecdote from someone attending a Lacanian conference a few years ago. An old school Lacanian shrink from Paris was giving a case presentation about a woman he was seeing. At a certain point in his presentation he began to talk about what the woman thought about when she masturbated. In the audience eyebrows were raised, a few people started shuffling in their chairs. At the end of his talk the startled chair asked him how he managed to get his analysand to admit these things to him. “Well”, he replied, “I asked her.”

By Owen Hewitson, LacanOnline.com

All content on LacanOnline.com is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

I understand Lacan’s intention in emphasizing the gap between signifier/ signified when insisting on silly questions, I.e. jean allough wedding asking who he got married. I found this intervention Unnecessarily artificially enforcing inquiry.

Gap brtween word and Object is no private on Lacan’s. Prominent scholars has been working on it since inaugural philosophy of language begun early 20th Century with Frege, Russell, Wittgenstein, and Vienne Circle. After World War II, W.V.Quine’s seminal paper “Two Dogmas on Empiricism” shows the path on this indeterminacy between what things really are and what we think those things are.

Through Godel’ incompleteness, Popper falsificationism, and W.V.Quine’s Duhem’s holism we witnesses about this gap.

What I found ridiculous is sustain this Jakobsonian – Heideggerian linguistic version (Lacan’s) under every circumstances, I.e. interpreting patients statements in this vein every friking time.

Sometimes stimulus are grouping as a whole in which case is possible articulate some verbal behavior (W.V.Quine’s Skinner’s behaviorism). Certainly, Gavagai doesn’t mean Rabbit in essence but point at Rabbit in some holophrasticaly approximate manner.

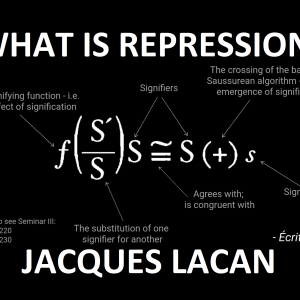

Question mark approach in Lacan’s Jakobsonian graph of desire reported in “Subversion of Subject and Dialectics of Desire” collected by American English Lacan’s Ecrits editor Bruce Fink, and graph developed through Seminar V, unveils not only indetermination between S/s, but juxtaposition of message and code. Message on the side of Subject, while code on the side of Other. After being Juxtaposed, message and code become mixed and unidentifiable. Subject is capture by the Other. Even though this rationalization, I found this conclusion very abstract and speculative. Where this Cognitive evrnts occur? Inside the brain? Or in some externalized articulatory apparatus ? The big question carry out with certain difficult by Chomsky’s Minimalist Program concerning interfaces modules is some problematic pending to be solved. Chomsky endorses internalist standpoint when approaching language acquisition origins. I stick around wondering learning experience and empirical objects. This is a huge unfinished debate. Lacan is on his way. His graph accomplishes to be remarkable piece of bubble-and-arrow cognitivism of his time.

1)The 2 above comments seem to ignore that Lacan primarily concerns himself with what is going on in an ANALYSIS session. If some of his observations can be applied to the world at large, that’s a cherry on the cake (i.e. a bonus). This reflects Freud’s “sometimes a cigar is just a cigar”. Except for a Kleinian of course.

2)$a represents a captured and privileged “scene” in a subject’s history. It is necessary and contingent. It is a metaphor of Das Ding. There is more to this matheme than Owen is letting on. For instance, why the losange as an operator? The original French word for this sign is “poinçon”. Why has it been translated in English as “losange”? What happens to a losange if you squeeze it? what is underneath it?

3)The early Lacan indeed put the accent on making possible a conscious enunciation of $a, which led to the idea of “crossing the fantasy”, in particular in relation to the Pass. Later on, from Sem 20 (Encore) onwards, Lacan put the accent on the “there is no sexual rapport”.