Shades of Subjectivity – II

This is the second of four article on the subject of subjectivity (the first is here).

Just as in the last article we opposed subjectivity to objectivity, so here we can oppose subjectivity to identity, both in ordinary parlance and in psychoanalytic terminology. Subjectivity is not reducible to identity. Identity is a purely imaginary category in Lacan’s work, and stems from Freud’s observations on identification. In a sort of shorthand way of bringing the difference between them into relief we can say that whilst a person’s identity is malleable and can change, subjectivity persists as irreducible and irrevocable.

Let’s start by positing an equation between the ego in Freudian terms and identity. One of the great lessons of psychoanalysis is that identity is coextensive with identification – the ego is simply the sum of all abandoned object cathexes, to use Freudian terminology, and as Freud puts it, “Identification is the earliest and original form of emotional tie” (SE XVIII, 107). By extension, this might be taken to imply that all subjectivity is constituted on the basis of inter-subjective relationships.

Lacan follows Freud in believing that our identity is constituted on the basis of successive, compounded identifications, the result of which we know as the ego. This is one of the key elements of Lacan’s theorisation of the imaginary register. However, Lacan highlights the consequences of a too close a dual-imaginary bond as malevolent and destructive in so much of his early work. He builds on Freud’s idea of a correspondence between identity with identification in his early work of the 1920s, ‘30s and ‘40s, but adds a darker twist. Identity is not something one has but something one develops in one’s relation to the other, to the imaginary counterpart. One’s identity is always therefore essentially a dual-imaginary identification that is borrowed from the other. And yet in all the work he presents at that time he privileges a certain violence, the destructive and homicidal consequences of the reality of identity formation. We need only think of his comments on the case of the Papin sisters, Aimée, and his work on aggressivity. What Lacan gives us amounts to the idea that the imaginary dimension can be characterised as the ‘hell of other people’, to paraphrase Sartre.

If there is a conflation of subjectivity with identity it is perhaps because of the overpowering push to identification that Freud highlights in his Group Psychology essays from 1921 (SE XVIII, 67) and that Lacan sees as constituting not just the structure of paranoia but, by extension, the structure of all human knowledge.

That one’s identity is defined in relation to the other is absolutely prevalent today, so much so that there seems no way in which identity, much less the subject, can otherwise be thought of. We are expected to see ourselves as someone’s employee, someone’s lover, someone’s husband, a positioning that Lacan drew attention to with his distinction between subject of the statement and the subject of the enunciation (something discussed elsewhere on this site).

Today, the requirement to think of ourselves in inter-relational terms has a new and perhaps more exacting character to the one Freud and Lacan were commenting on. In our time, the predominant mode of inter-relational interaction is realised through the network, and via a very recent medium. Indeed, Jacques-Alain Miller, in his commentary on the recently-published Seminar VI (which he edited) cited the network as a new form of social discourse distinct from that of patriarchy:

“We are in the process of leaving the age of the Father. Another discourse is in the process of supplanting the old one. Innovation in the place of tradition. Rather than hierarchy, the network.” (Blurb to Seminar VI, Desire and its Interpretation, translation from the French my own).

The kind of linear identifications that Freud and Lacan saw in hierarchy are now found to be much more diffuse through the network. We can see how this shift is redefining identity simply in the change of vocabulary that accompanies it – modern day terms such as ‘identity theft’ denote how a totally digitalised experience simulates a kind of pure big Other because ‘identity theft’ entails the loss of who you are – without your digital identity you are simply not known to the Other. Likewise, Facebook only allows an account holder a single account so as to be commensurate with their identity, and Google Plus describes itself, using a slightly sinister term, as an ‘identity service’ rather than a social network. This kind of identity promises a means to express individuality – that you can share your thoughts and experiences whenever you choose. For some, this is the very essence of subjectivity. But isn’t the expression of individuality far too often just the compensation offered us by capitalism for the price we pay with our subjectivity? As the now rather worn truism goes, if you’re not paying for it, you’re not the consumer, you’re the product. The odd thing is perhaps that this does not lead to a confusion of identity but of a solidification of it.

On what grounds then can we justify any reference to subjectivity and try to distinguish it from identity?

A distinction between the two that is at least implied if not fully articulated can be found in both Freud and Lacan’s work. If in the Group Psychology papers of 1922 Freud is referring to identity as the result of identification, mulling over its darker side in terms of human susceptibility to worship a leader, a few years later he is doing something very different when he makes his pronouncement in the New Introductory Lectures that “Where It was, there must I come to be”, the infamous Wo Es war… statement (SE XXII, p.80). And if we take Lacan’s observation about this formula seriously – in which he criticises Strachey’s translation of “Where id was, there ego shall be”, noting that Freud does not put the articles on the pronouns, does not say ‘Where the id was, there must the ego be – we can see that Freud is making an ontological statement. What is at issue here is something quite precise, quite different to the question of identity as he phrased it earlier. Interestingly, we find the same distinction in Lacan. It is as if both Freud and Lacan follow the same trajectory of pointing to the imaginary aspect of identity and its darker side (Freud’s analysis of the crowd; Lacan’s thesis on paranoia and the mirror stage), but then turning to privilege an ontology grounded in something more formally impersonal (Freud’s Es or It and Lacan’s big Other/symbolic order).

This formality through impersonality marks the move from identity to subjectivity in both Freud and Lacan’s work. Jacques-Alain Miller has elaborated on how Lacan treated this, drawing attention to a term that Lacan uses infrequently in his work, but expresses this idea in a beautifully compact way: that of ‘extimacy’. The idea of ‘extimacy’, a portmanteau of ‘extimate’ and ‘intimacy’ expresses precisely the radical alteration to the subject’s sense of self, the subject’s ‘me-ness’, that Freud is articulating in the move from identification to the Es. As Miller writes,

“If we use the term extimacy in this way, we can consequently make it be equivalent to the unconscious itself. In this sense, the extimacy of the subject is the Other. This is what we find in ‘The Agency of the Letter” (Écrits, 172), when Lacan speaks of “this other to whom I am more attached than to myself, since, at the heart of my assent to my identity, to myself, it is he who stirs me” (translation modified) – where the extimacy of the Other is tied to the vacillation of the subject’s identity to himself. Thus the writing A—> $ is justified.” (Miller, ‘Extimacy’).

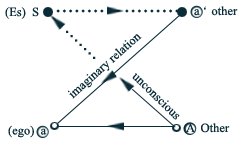

We can also use Lacan’s own Schema L from the Rome Discourse to express this as a movement from a > a’ (identity founded on an imaginary identification with the other) to A > $ (a subjectivity that is radically Other, extimate.)

But what sense does it make to say that the subject is to be found in the Other? If subjectivity is distinct from identity but both are founded on different types of alienation, is subjectivity anything substantive? Levi R. Bryant offers some reflections on this question worth quoting in full:

“… The Lacanian subject is quite literally a void or emptiness. It’s a sort of empty point, a mobile empty space, that language can never fill. Symptoms are perpetual (failed) attempts to fill that a priori hole. In this regard, the Lacanian subject is the ruin of every identity or attempt to ultimately say what we are.

…

As Lacan argued, language introduces something into the world that wasn’t there before for the biological human being: constitutive absence. Constitutive absence is not the absence of this or that thing, such as being out of coffee in the morning, but is a sort of a priori or transcendental absence…. Most importantly, it is an absence that can never be filled. Consider the sliding puzzle game [featured here]. Notice the empty square? That empty square allows the substantial squares to be moved about and combined in a variety of different ways, creating a variety of different patterns. However, the square itself will never be filled. It will always be empty no matter how much we slide the other squares about. The various combinations of squares and the patterns they create can be thought as formations of the unconscious. As the mobile and empty square moves about, it creates different patterns or formations. The empty square, by contrast, can be thought as subject. This is how it is within the Lacanian framework. Subject, transcendental absence, is nothing substantial, nor it is an agency that you are directing like a little homunculus. Rather, it is that which is perpetually shifting about in the system of language, creating all sorts of nutty formations.” (source)

Jacques-Alain Miller has come up with an idea of what subjectivity in this (minimal, depreciated) form might look like in his game-changing article Suture (read a summary of his argument on this site here). Under a logic which Miller borrows from Frege the subject is conceptualised independently of any consciousness, psychology or agency. Miller presents the subject as empty place, co-extensive with a zero-signifier. Only as such can the subject have a place in the structure of the Other. An effect of the fact that the subject evades representation in language, as Bryant points out above, it can only be represented to other signifiers as a zero. This is the way that Miller understands Lacan’s famous formula ‘the signifier represents the subject for another signifier’: the signifier represents the subject in the same way that zero as a number represents lack, or ‘nothing itself’, as a concept. This gap, lack or absence itself can then count as absence, as one, and thus be represented signifier to signifier. As I have argued more fully elsewhere about Miller’s conception of the subject in this paper, the subject in this sense also effectively animates the signifying chain itself. In the same way that the pieces of the puzzle in Bryant’s diagram referred to above can only move if there is an empty square, so the structure needs a representation of a lack in order for the differential nature of the signifying chain to be realised, for the structure to become mobile as such.

We can conclude with a third expression of this idea, this ‘shade’ of subjectivity, in the form of an anecdote taken from Slavoj Zizek’s best work on the topic of Lacanian psychoanalysis:

“At an art exhibition in Moscow, there is a picture showing Nadezhda Krupskaya, Lenin’s wife, in bed with a young member of the Komsomol. the title of the picture is ‘Lenin in Warsaw’. A bewildered visitor asks a guide: ‘But where is Lenin?’ The guide replies quietly and with dignity: ‘Lenin is in Warsaw’.” (The Sublime Object of Ideology, p.159).

The point of Zizek’s anecdote is to show that the title of the painting names the object that is missing in it. The visitor’s mistake is to assume that the title is talking about what is in the picture. For Zizek, the painting’s title is equivalent to what Freud calls Vorstellungreprasentanz, often translated as ‘representative of the representation’, which Zizek defines as “the representative, the substitute of some representation, the signifying element filling out the vacant place of the missing representation”, or of the depiction of Lenin in the painting (The Sublime Object of Ideology, p.159). The title of the painting thus has a structural equivalence to the missing square in Bryant’s illustration – the only difference is that in Zizek’s apologue the title itself is the signifier of lack, of a lack in the Other. A signifier of this sort does not represent an object as such (the empty square, Lenin in the bed) but precisely the lack of an object.

In the next article we will look at a third ‘shade’ of subjectivity which can help us find our way between the two ontological definitions of subjectivity presented in the latter part of this article: between, on the one hand, an ‘experiential/phenomenal’ subjectivity; and on the other, a ‘formal’ subjectivity without agency that amounts to the mark of a lack. To step back from all this abstract theorisation to the level of the psychoanalytic clinic, the question can be phrased as: what kind of subject presents itself to a psychoanalyst in the consulting room? Is there anything more substantial to this subject beyond the marker of an empty place, or is there nonetheless an experiential/phenomenal subject that it’s worth making the case for? We will look at how a psychoanalysis might address what Lacan refers to as “the subject’s sense of life” (Ecrits, 558), and whether this sense of life is nothing more than the exchange of one alienation (in imaginary identifications) for another (in language). If this doesn’t suppose an agency for the subject, the question which follows is one that preoccupied Lacan throughout Seminar XI (spurred by an intervention by Miller): what kind of ontology are we dealing with in subjectivity?

By Owen Hewitson, LacanOnline.com

All content on LacanOnline.com is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

Leave a Reply